Polynomial Effects

(Marcello Gallucci)

keywords Non-linear regression, Polynomial model, non-linear effects, linear model

GAMLj version ≥ 1.5.0

In this example we work out an example of polynomial regression in the GLM, using jamovi GAMLj. Data are (simulated data) here.

The research design

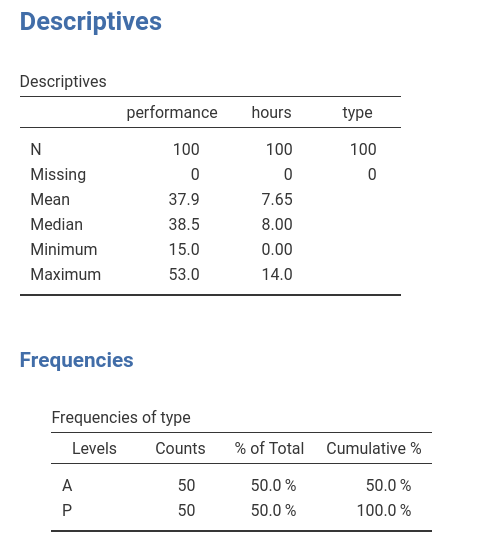

The dataset has three variables of interest. Imagine we measured

athletes performace in a match using a standard scale and the number of

hours they trained in a week. The idea is to study the relationship

between hours of training and performance. Because training can be good

for performance but training too much may have detrimental effects on

performance, we foresee a non-linear effect of training hours on

performance. Furthermore, athletes are divided in two groups (variable

types), professionals (P) and amateurs

(A), and we want to check if the effects of training is

different in the two groups.

Non-linear (polynomial) effects

Input

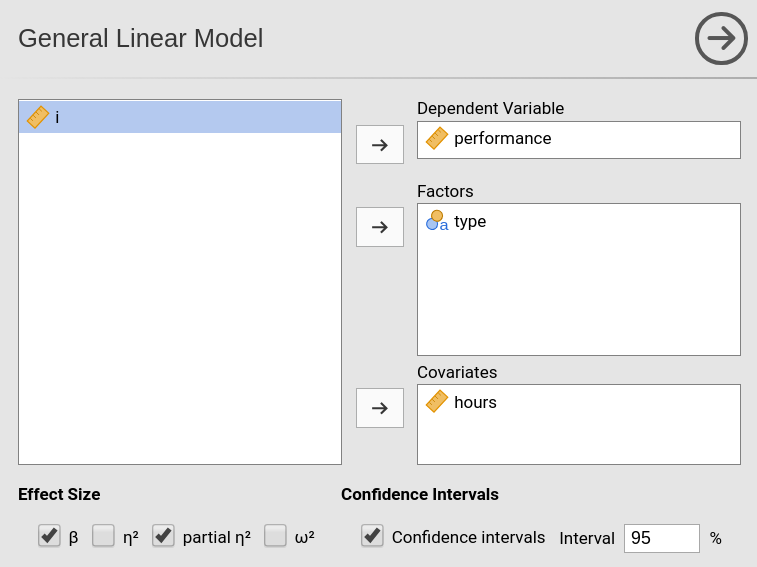

We first set up a linear regression with only linear effects. We

launch General Linear Model from the

Linear Models menu. We put performance in the

dependent variable field and hours in the

covariate.

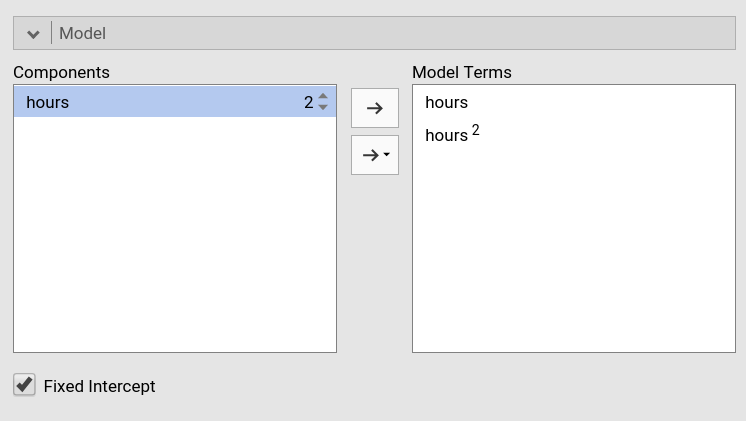

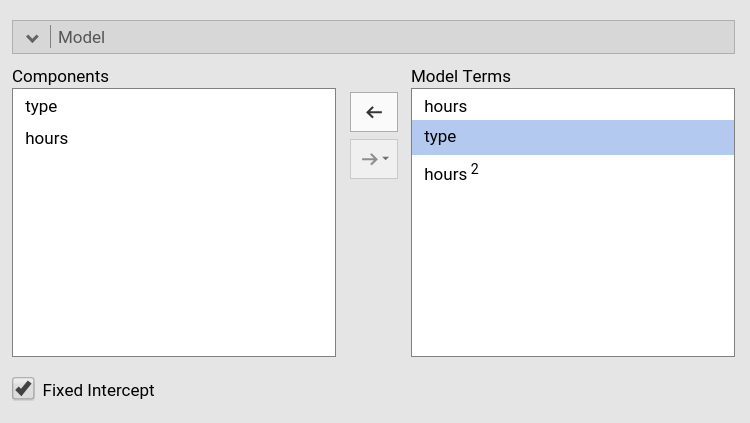

By defining the variables we obtain a simple regression in the

output, but we want to specify a quadratic effect of hours,

so we go to the Model panel. As soon as we select

hours in the Components field, we can see on

the right of the variable a little 1 appearing.

That little number indicates the order of the effect that we want to

insert in the model, that is, the exponent of the term we want to

include. The number 1 (default) means linear

effects. To include a quadratic effect (second order), we should

increase the number to 2, as in the Figure. We can then

push the arrow to move the quadratic term into the model.

If we want, for instance, also the cubic term, we should increase the

number to 3 and move it to the model as well.

Results

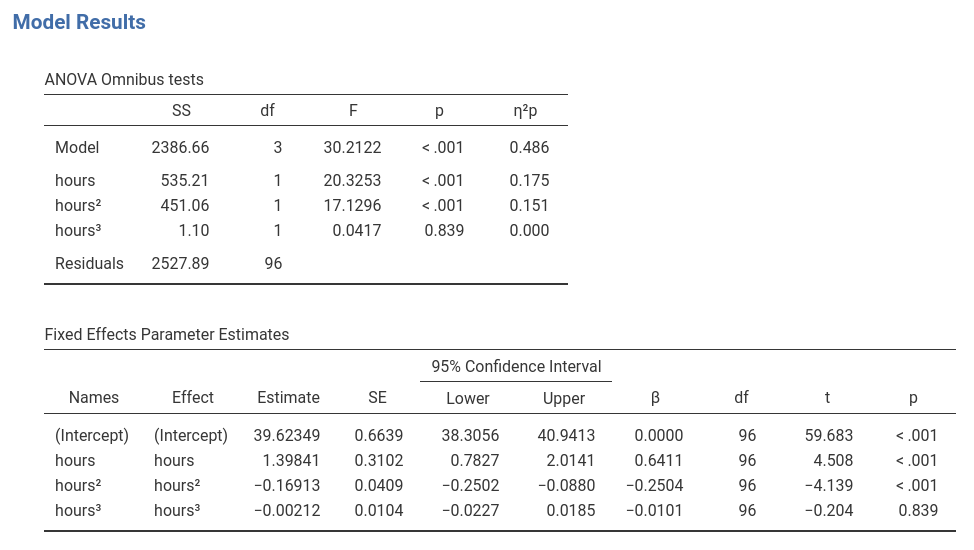

Results show that the polinomial (linear+quaratic+cubic) effects of

hours on performance explain about 50% of the

variance \(R^2=.486\).

BY inspecting the F-tests and the estimates (B coefficients) we can

see that we have a linear (\(hours\)) and a quadratic (\(hours^2\)) effect of hours to

performance, whereas the cubic effect (\(hours^3\)) is trivial and can be

disregarded (the \(\eta^2p\) is

practically zero).

When it comes to polynomial models, the best way to figure out the

relationship between variables is to plot the effects. We can do that by

selecting the Plot panel and by putting hours

in the Horizontal Axis field (mind that in GAMLj default

the IV is centered to its mean, to obtain a nice plot I changed the IV

scaling to none in Covariates scaling

panel).

We can see that, on average, up to 10 hours, one more hour of training is good for the performance, but after 10 hours, increasing training is not advantageous in terms of performance. That is, we have a curvilinear effect of the IV on the DV.

Conditional polynomial effects

We can now analyze possible differences due the the type of athletes

by introducing type as a factor in the model.

When we go to the Model panel, we see that the main

effect of type is automatically inserted in the model

terms.

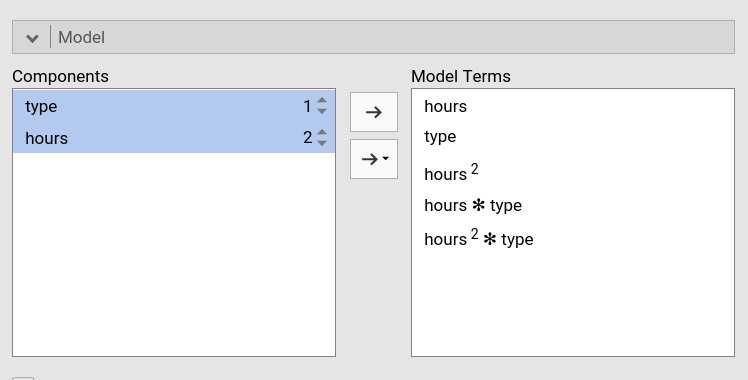

However, we want to see if the effect of hours depends

on type so we need to include the interactions. We need two

interactions: the interaction linear hours by type,

and quadratic hours by type (I removed cubic

hours based on the previous analysis).

For the linear by type interaction, we select both

type and hours and we press the

arrow to move the interaction term to the

Model Terms field.

For the quadratic by type interaction, we select

both type and hours, and we increase the

exponent of hours to signal that we want the quadratic term

to interact with type. We press the arrow to

move the interaction term to the Model Terms field.

We have done setting the new model.

Results

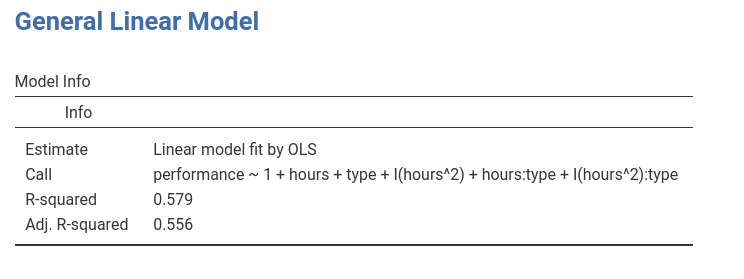

The model info table shows the actual R-syntax model we estimated and the \(R^2\), the latter clearly larger than the \(R^2\) of the previous model.

As regards the effects, we can see that we do have a quadratic

hours by type interaction, so we can say that the effect

of hours on performance has a different shape

depending on the type of athlete.

Inspecting the plot makes the interpretation easier.

For professional athletes (P), the performace increases

along hours of training almost linearly, thus the more hours they train,

the better the performance. For amateur athletes (A) the

performance is positively linked to training hours up to 9 hours, after

which more training means a strong decrease in performance. Thus, for

amateurs there’s a U-shaped effect of training on performance, whereas

for pro’s the relationship is practically linear.

Simple effect analysis (Advanced)

Input

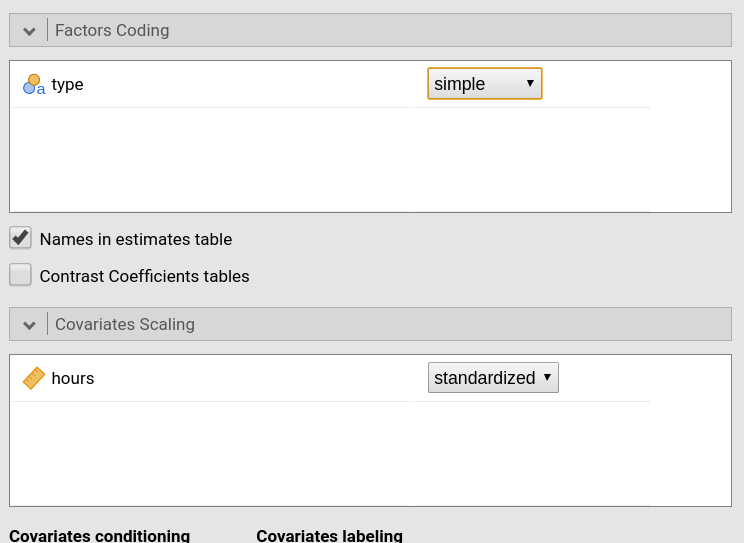

Assume we want to test groups differences along the training hours

continuum. That is, we want to test the difference between the two

groups at different levels of training length. To do that, it is

convinient to rescale the variables: We standardize the independent

variable and code the factor with simple coding, which

yields coefficients associated with the factor equal to the groups

difference in the expected value of the dependent variable.

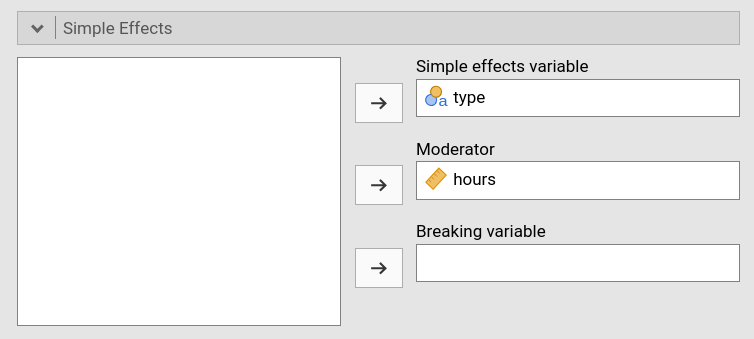

We then ask for the simple effects of type for different

levels (mean and mean plus/minus one SD) of hours.

Results

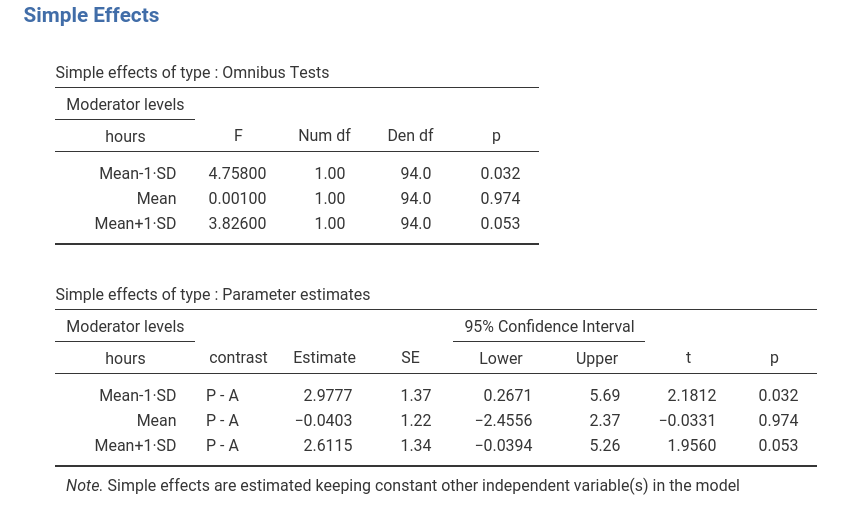

The simple effects tables show that for low (-1SD) and high (+1SD)

training the groups are statistically different and the difference is to

the advantage of the Professional group (\(P-A=2.977\) and \(P-A=2.667\)), whereas for average training

the performance does not seem to be different between the two groups

(\(P-A=-0.0403\)). By changing the

covariate conditioning in the Covariate Scaling panel one

can test these differences for all values of hours that one

wishes.

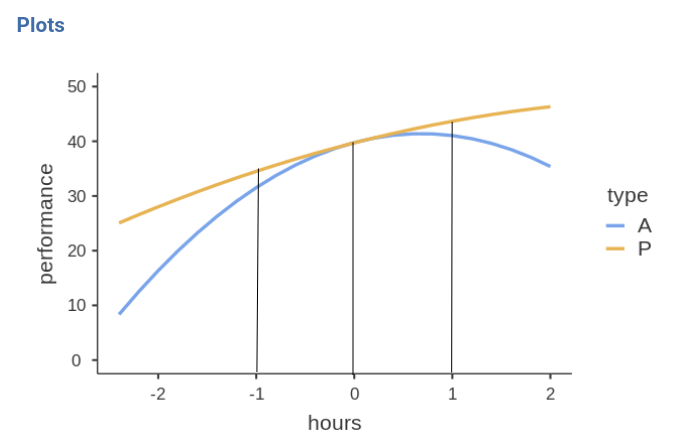

To visualize what we are doing, let’s see the plot after standardizing the IV.

In practice, the simple effects tests we have seen tested the

difference between the blue and the yellow curve at hours

equal to -1, 0, and 1 . Because we standardized hours,

those values correspond to -1SD, mean, and +1SD of training hours.